![]()

This is our second post in a series that digs deeper into the thinking and application of the Inclusive Design Principles. It follows on from the first post Be Consistent.

In this article we’ll be looking at the principle of providing a comparable experience:

“Ensure your interface provides a comparable experience for all so people can accomplish tasks in a way that suits their needs without undermining the quality of the content.”

There are two crucial words in the description above: comparable and quality.

Comparable

Comparable: of equivalent quality; worthy of comparison.

We normally talk about equivalent experience when it comes to accessibility: ensuring diverse users have an equivalent or equal user experience to all other users. This is the goal but in reality is this 100% possible 100% of the time?

Let’s look at a couple of scenarios. If I am blind I can access a movie using Audio Description (AD). Everything that is visually editorially significant is described in a separate audio track so I can fully understand the plot of the movie. But can this replace seeing the expression on an actors face in a comedy or a thriller? Is it genuinely an equivalent experience?

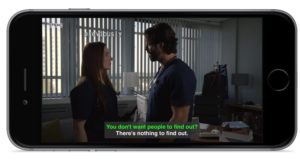

If I am deaf and cannot hear the soundtrack to a movie I can read the Closed Captions (CC). All speech is transcribed as well as editorially significant sounds and lyrics for music. So far so accessible but is my experience equivalent to someone who can hear the soundtrack? Music can change the atmosphere of a scene in a film drastically. Conveying that visually, via text or signing, is problematic.

The film Dunkirk is a great example of how music changes the atmosphere and pace of a movie as it uses a technique called Shepherd Tones in its soundtrack. Wikipedia describes a Shepard Tone as follows:

A sound consisting of a superposition of sine waves separated by octaves. When played with the bass pitch of the tone moving upward or downward, it is referred to as the Shepard scale. This creates the auditory illusion of a tone that continually ascends or descends in pitch, yet which ultimately seems to get no higher or lower.

As the video below explains the sound illusion makes Dunkirk incredibly intense; so intense that you’re on the edge of your seat in a constant state of apprehension that something bad is going to happen. I found it almost unbearable and the film profoundly difficult to watch. I came away from the cinema thinking ‘How on earth could you provoke that level of intensity to someone who is deaf using Closed Captions’?

Source: The sound illusion that makes Dunkirk so intense via Vox

Images are another crucial area of experience for all users including blind users. Typically we categorise and write alt text for images as follows:

- Decorative – an image that doesn’t convey information or is described elsewhere on the page and therefore can be hidden from the screen reader user

- Editorial – an image conveys information that is not conveyed elsewhere on the page and therefore must be described to the screen reader user

- Functional – an image that performs an action, such as opens a new page or triggers a change on the page, whose purpose must be described to the screen reader user

As Léonie Watson says in her blog post text descriptions and emotion rich images decorative images come in different forms. Horizontal rules, bullets or boarders presented as images have no need for a text alternative but what about ‘vibrant, emotion rich images that provide a website with a sense of atmosphere’? This is the look and feel, branding, and personality of a website. Léonie argues that many blind people, especially those who’ve had sight, appreciate a little personality coming through via the alt text as it helps build a more comparable user experience.

On the Inclusive Design Principles website, we have an image of three hot air balloons in the sky. It isn’t a logo or a link and could be categorised as decorative but we put it there visually for a reason – to provoke a response in the user. If it’s there visually why not convey this to a screen reader user? This is why it has the alt text ‘Three hot air balloons hang together in a calm, sunny sky’, to recreate the atmosphere we were aiming for visually. As Léonie says:

I used to have sight so I appreciate descriptive alt text on decorative images.

![]()

It’s is important to respect difference, however. No single person’s experience of disability is the same as another. People who’ve never had sight may find it hard to connect with text alternatives that use highly visual language as Victor Tsaran found out when he visited my home city of Brighton. When he visited Brighton Pavillion he picked up an audio guide – the alternative format for someone who is blind. But he found it unhelpful as it used visual language to describe the rooms that meant nothing to him. He wanted an alternative format that described how people lived in the Pavillion, provided stories and anecdotes. Something that he could relate to.

When we were writing the Inclusive Design Principles and the principle of comparable experience we felt that while it was possible to achieve equivalence much of the time it is not possible all of the time. Words, either written or heard, will not always adequately describe what is visible or audible to blind or deaf users. This is why the second word, quality, is crucial.

Quality

Quality: The standard of something as measured against other things of a similar kind; the degree of excellence of something.

Just because we can’t always provide an equivalent experience it doesn’t mean we don’t strive for quality, or ‘excellence’. Again this is where we evolve from accessibility to inclusion. Providing a comparable experience is rooted in providing a quality experience.

Quality can be measured in terms of the value of features to the end user, editorial, and efficiency of the interface. By considering the value (another Inclusive Design Principle) of features and how they improve the experience for diverse users you increase the quality of user experience.

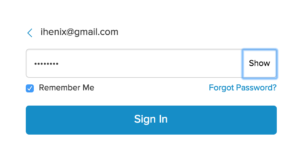

Take, for example, inputting passwords. In his blog post what I have learnt about motor impairment James Williamson discusses the challenges he has inputting passwords. James has Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), the illness that was the focus of the awareness raising Ice Bucket Challenge in 2014. He uses a combination of voice and a single finger to input text. No matter how accessible the password input field is the experience of inputting complex passwords that require a combination of upper and lower case letters, numbers and special characters can be difficult and frustrating. As James says when you can’t see and double check everything before hitting submit it can lead to a ‘high degree of failure’. Adding a ‘Show’ password button to reveal the password allows James to accomplish the task in a way that both suits his needs and ensures efficiency.

Quality is also a differentiator between making something compliant and making it inclusive and a pleasure to use. Let’s go back to Closed Captions. To be compliant with WCAG Level A and AA, Closed Captions must meet the following:

1.2.2 Captions (Prerecorded): Captions are provided for all prerecorded audio content in synchronized media, except when the media is a media alternative for text and is clearly labeled as such. (Level A)

This is not sufficient however for ensuring that CC are usable. In fact, it is entirely possible that an older user with deteriorating hearing and eyesight may not be able to read the CC. Many users may not be able to understand who is speaking without colour coding the captions of speakers. Font size, styles, positioning, editorial, colour coding can all make or break the experience. To understand more about creating a comparable experience for CC, or subtitles as they are known in the UK, see the excellent BBC Subtitle Guidelines.

Audio description can also vary in quality. To be compliant with WCAG Level A and AA, Audio Description must meet the following:

1.2.5 Audio Description (Prerecorded): Audio description is provided for all prerecorded video content in synchronized media. (Level AA)

Like with CC meeting this WCAG requirement does not mean we have a comparable experience, however. Quality and comparable experience come in many forms such as good editorial, accurately describing what is relevant, or using a voice that is appropriate to the nature of the movie or programme.

Taking it a step further quality a better experience can also come from providing Integrated Described Video (IDV) rather than Audio Description. Instead of being a separate audio track describing editorially significant visuals (AD), IDV naturally describes everything in the main audio track.

This first video is an example of Audio Description:

Source: Described video (DV) Example: “Show Me Your Art” via Accessible Media Inc

This is the same video but the voiceover is Integrated Described Video:

Source: Integrated Described video (IDV) Example: “Show Me Your Art” via Accessible Media Inc

This is a fantastic way to produce educational and instructional video. Not only does it benefit users who are reliant on AD but also sighted users as it conveys the same information visually and verbally making it easier to follow and learn.

I want to shout the next two sentences across the rooftops because I think this is so important and we have a huge opportunity to be both innovative and inclusive here: I would love to see the likes of BBC, Netflix, Amazon and more commission new content with a goal of having editorially visible content integrated into the natural speech of the soundtrack. We do this for plays on the radio after all. This would also benefit deaf users as the text is made available through closed captions.

Comparable experience in practice

As with all the Inclusive Design Principles, providing a comparable experience will be more successful if it is designed from the outset. Project Owners, visual designers, interaction designers, user experience people, content editorial, and even marketing should all be thinking about how diverse users will experience your product early on in the design phase. That way you can commission images that lend themselves to good alt text or commission multimedia that uses IDV rather than having to shoehorn AD into a separate soundtrack.

Finally, the following video is probably the most impressive example of comparable experience: How sign language innovators are bringing music to the deaf. Sign Language Interpreter, Amber Galloway Gallego, describes how she turns a hearing centric music world into a visual one. Rather than just focusing on the lyrics and therefore making it accessible, she also focuses on the sounds – base, rhythm, rhyme, rap, holding a note – and how she interprets that into a comparable visual experience.

This is a great example of how you can’t have an equivalent experience listening to music if you are deaf but the experience can be comparable given the exceptional quality of sign language interpretation.

The full list of principles and related blog posts are:

- Provide a comparable experience

- Consider situation

- Be consistent

- Give control

- Offer choice

- Prioritise content

- Add value

A full explanation of each principle can be found on the Inclusive Design Principles site.

Comments

Really interesting article, and the work Amber is doing with signing music is brilliant. I’ve never really thought about the difference between someone who has lost their sight compared to people who have never seen before, I’ll certainly have that in my mind now when deciding if an image is decorative or not.